BEIJING — A Chinese-led research team has discovered a surprisingly huge stellar black hole about 14,000 light-years from Earth — our "backyard" of the universe — forcing scientists to re-examine how such black holes form.

The Milky Way galaxy is estimated to contain 100 million stellar black holes — cosmic bodies formed by the collapse of massive stars and so dense even light can't escape. Until now, scientists had estimated the mass of an individual stellar black hole in our galaxy at no more than 20 times that of the Sun.

But the new discovery has toppled that assumption.

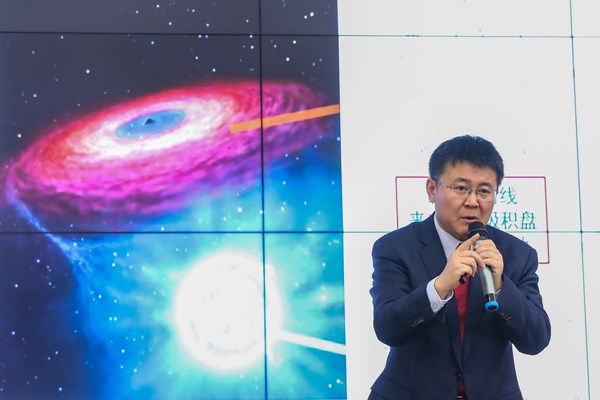

The team, headed by Liu Jifeng, of the National Astronomical Observatory of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (NAOC), spotted the black hole, which has a mass 70 times greater than the Sun. Researchers named the monster black hole LB-1.

The discovery was a big surprise. "Black holes of such mass should not even exist in our galaxy, according to most of the current models of stellar evolution," said Liu.

"We thought that very massive stars with the chemical composition typical of our galaxy must shed most of their gas in powerful stellar winds, as they approach the end of their life. Therefore, they should not leave behind such a massive remnant. LB-1 is twice as massive as what we thought possible. Now theorists will have to take up the challenge of explaining its formation."

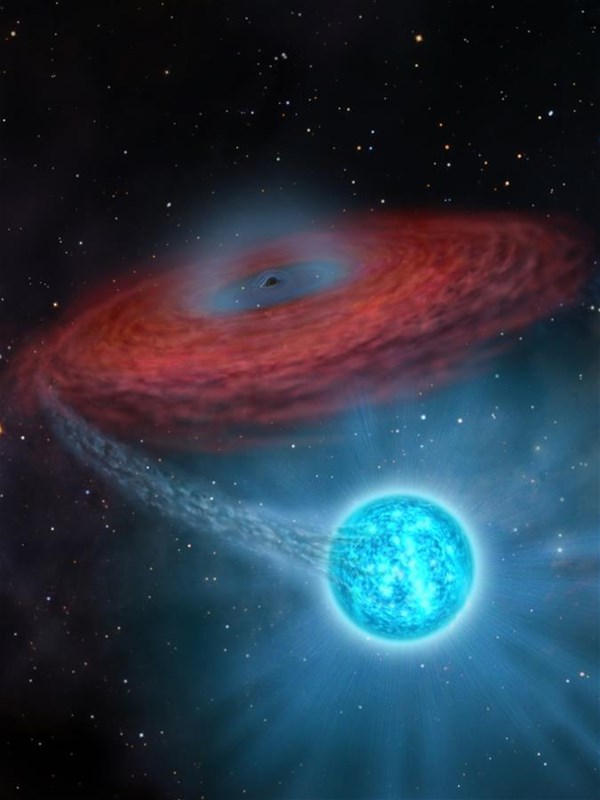

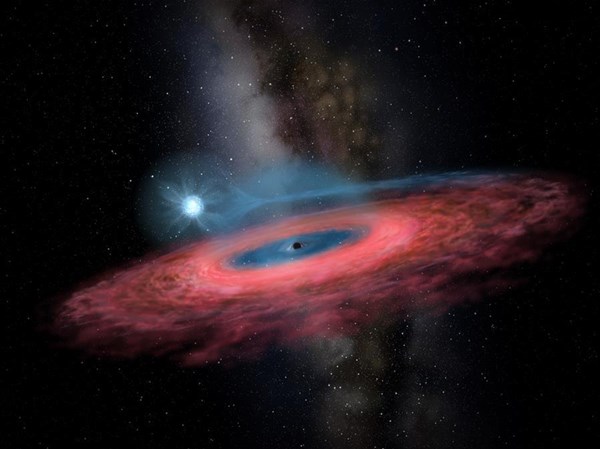

Until a few years ago, stellar black holes could only be discovered when they gobbled up gas from a companion star. This process creates powerful X-ray emissions, detectable from Earth, which reveal the presence of the collapsed object.

The vast majority of stellar black holes in our galaxy are not engaged in a cosmic banquet though, and thus don't emit revealing X-rays. As a result, only about 20 galactic stellar black holes have been accurately identified and measured.

To counter this limitation, Liu and his team surveyed the sky with China's Large Sky Area Multi-Object Fiber Spectroscopic Telescope (LAMOST), looking for stars that orbit an invisible object, pulled by its gravity.

This observational technique was first proposed by the visionary English scientist John Michell in 1783, but it has only become feasible with recent technological improvements in telescopes and detectors.

Still, such a search is like looking for a needle in a haystack: only one star in a thousand might be circling a black hole.

After the initial discovery, the world's largest optical telescopes — Spain's 10.4-meter Gran Telescopio Canarias and the 10-m Keck I telescope in the United States — were used to determine the system's physical parameters. The results were fantastic: a star eight times heavier than the Sun was seen orbiting a 70-solar-mass black hole every 79 days.

The discovery of LB-1 fits nicely with another breakthrough in astrophysics. Recently, the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) and Virgo gravitational wave detectors have begun to catch ripples in space-time caused by collisions of black holes in distant galaxies. Intriguingly, the black holes involved in such collisions are also much bigger than what was previously considered typical.

The direct sighting of LB-1 proves that this population of over-massive stellar black holes exists even in our own backyard. "This discovery forces us to re-examine our models of how stellar-mass black holes form," said LIGO Director David Reitze from the University of Florida in the United States.

"This remarkable result along with the LIGO-Virgo detections of binary black hole collisions during the past four years really points toward a renaissance in our understanding of black hole astrophysics," said Reitze.

Scientists from China, the United States, Spain, Australia, Italy, Poland and the Netherlands participated in the research.

Liu said the research team aims to utilize the LAMOST to discover nearly 100 black holes within the Milky Way in the coming five years.

The discovery is reported in the latest issue of the academic journal Nature.