The Palace Museum in Beijing is one of the country’s first UNESCO World Heritage sites. [Zhuo Ensen / for China Daily]

Preservers of Chinese heritage gathered at Palace Museum in Beijing last week to celebrate 70 years of the founding of UNESCO and the 30th anniversary of China’s ratification of the World Heritage Convention.

The Palace Museum, which is also known as the Forbidden City, the Mogao Caves in Northwest China’s Gansu province, and sections of the Great Wall were among the first six Chinese locations to be declared UNESCO World Heritage sites in 1987. With 48 today, China has the world’s most such sites after Italy.

“China’s World Heritage sites differ in types and landscapes, which is admired by the whole world,” says Du Yue, secretary-general of Chinese National Commission for UNESCO.

“In the past decades, government bodies and the private sector have both cooperated with UNESCO (to declare such sites).”

In China, protection of UNESCO World Natural Heritage is supervised by Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, while the State Administration of Cultural Heritage is in charge of works related to World Cultural Heritage sites.

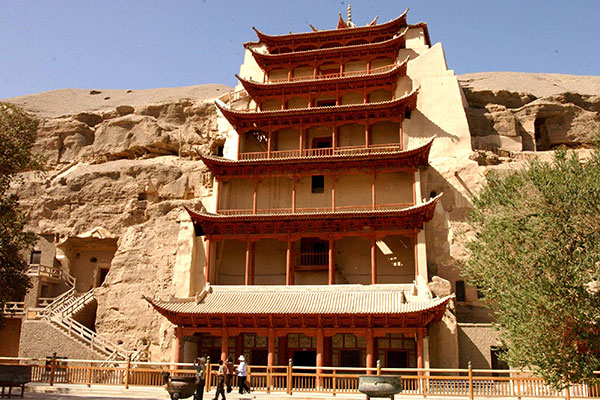

The Mogao Caves, a UNESCO World Heritage site in Gansu province, is a witness to the cultural exchanges on the Silk Road. [Xin Lei / for China Daily]

Lu Qiong, deputy director-general of sites’ protection and archaeology under the State Administration of Cultural Heritage, says China’s sites are distributed across wide geographical locations such as the Great Wall, stops along the ancient Silk Road and the Grand Canal.

“China’s cultural heritage preservers at all levels have nurtured expertise in protection, management, academic studies, supervision and display of these sites,” Lu says.

She cites the restoration of the Great Wall, which is more than 20,000 kilometers, among such major works.

China’s nationwide World Heritage supervision and warning system for natural decays of such property or man-made damages is still under construction, Lu says.

Annual reports and collection of data will be needed to refine the management.

Better guidance keeps coming for grassroots staff overseeing heritage locations. Chinese versions of four UNESCO World Heritage resource manuals concerning disaster prevention and management issues were released last week after five years of preparations and translation.

Lu Ye, a project officer for culture at the UNESCO’s Beijing office, says a national training program, which combines efforts of different departments under the central government and the country’s top academic institutions, will be launched in 2016 to generate expertise in World Heritage under an established framework.

“The World Heritage Convention cannot cover each country’s needs in detail,” Lu Ye says.

“We expect relevant work to be done at a nation level.”

One focus of the program will be sustainable tourism development at the sites.

The inclusion of the Silk Road as UNESCO World Cultural Heritage with Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan demands cross-border coordination by Chinese preservers.

And international teams have long participated in the protection of such sites.

Now Chinese heritage preservers have more responsibilities beyond the national borders.

“The world is not peaceful,” says Shan Jixiang, director of the Palace Museum, adding that the protection of World Heritage is gaining more significance today.

“I’ve visited those admirable cultural heritage sites in Iraq and Syria. But they are being destroyed not during war, but due to sabotage.

“It’s time for human beings to condemn such vicious deeds and protect heritage.”

The Chinese have joined in cultural heritage restoration overseas in recent years. For example, they have played crucial roles in restoration projects in Angkor Wat in Cambodia and Samarkand in Uzbekistan.

“These efforts reflect our growing strength in heritage protection,” says Lyu Zhou, a professor from the School of Architecture at Tsinghua University in Beijing. “We need a bigger international arena to play our roles.

“But it’s important to focus on our own heritage issues to better promote our culture,” he says.