The recoverable capsule of China’s first microgravity satellite, SJ-10, lands safely on Earth on April 18, marking a step forward in the country’s space science research.[Photo/Xinhua]

The returning capsule from SJ-10, China’s first microgravity satellite, landed safely at 4:30 pm on April 18 in Siziwang Banner, in the Inner Mongolia autonomous region.

Resembling the shape of a bullet, the SJ-10 modules carried 19 experimental loads that sought to shed light on microgravity and bioscience. Eleven of the experimental loads were aboard the returning capsule following its 12 days in orbit. The other eight will remain in orbit for a few more days aboard SJ-10’s orbital module.

A helicopter transports the re-entry capsule of China’s first retrievable microgravity satellite SJ-10 in Siziwang Banner, north China’s Inner Mongolia autonomous region, April 18, 2016.[Photo/Xinhua]

“The returning capsule brought back nine bioscience experimental loads and two microgravity experimental loads,” said Duan Enkui, deputy chief designer of scientific application systems on SJ-10 and a professor at the Institute of Zoology affiliated with the Chinese Academy of Sciences. “So far, all the experiments are going well, and some have already produced surprising achievements.”

On April 17, Duan’s team announced that high-resolution images sent back from the satellite enabled scientists to prove that early-stage mouse embryos could develop fully into blastocysts. It was the first time such an experiment had been successfully conducted.

Scientific personnel work at the landing area of the re-entry capsule of China’s first retrievable microgravity satellite SJ-10 in Siziwang Banner, north China’s Inner Mongolia autonomous region, April 18, 2016. [Photo/Xinhua]

“Embryonic development starts from a single-cell fertilized egg, which divides into two cells, four cells, eight cells, ... until it forms a blastocyst that can be implanted in the womb,” he said.

“Now, we have proved that this important process of embryonic development is possible in a space environment. Maybe, next time, if we have a returning capsule that stays in orbit for three or four days, we will actually be able to transfer the blastocysts into females and see the birth of space mice.”

The embryos completed the whole development process within four days of the launch, but the returning capsule had to spend 12 days carrying out other experiments before it could head back to Earth. So scientists used chemicals to fix the developed blastocysts so they could carry out further analysis after their recovery.

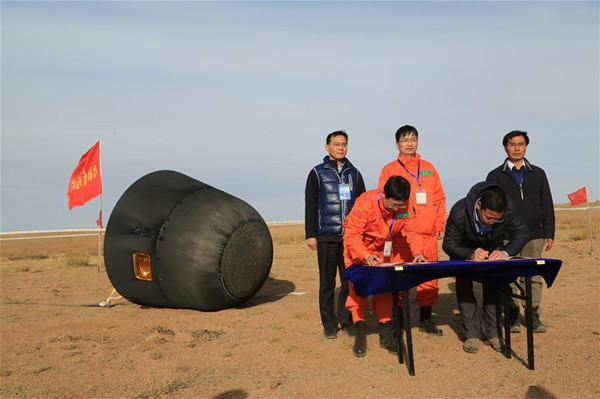

Scientific personnel sign for handover of capsule at the landing area of the re-entry capsule of China’s first retrievable microgravity satellite SJ-10 in Siziwang Banner, north China’s Inner Mongolia autonomous region, April 18, 2016. [Photo/Xinhua]

Scientists collected data from other experiments during the 12 days in orbit.

For example, they lit organic glass and polyethylene materials inside one of the experimental loads and received data and images related to the burning process.

The experiment is aimed at understanding the risk of fire on manned spacecraft.

According to Wang Shuangfeng, an assistant researcher from the Institute of Mechanics affiliated to the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the person in charge of the burning experiment, the combustion process in the weightlessness environment of space is different to that on the ground.

Scientific personnel work at the landing area of the re-entry capsule of China’s first retrievable microgravity satellite SJ-10 in Siziwang Banner, north China’s Inner Mongolia autonomous region, April 18, 2016.[Photo/Xinhua]

“We have to figure out the fireproof properties of nonmetal materials so as to draw up usage standards and prevention protocols to ensure astronauts’ safety,” Wang said.

After the recovery of the returning capsule, more in-orbit experiments will be conducted, including larger scale combustion tests.

Hu Wenrui, the chief scientist for the SJ-10 project and a member of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, said the recoverable capsule gives China an advantage in microgravity research.

“With the recoverable capsule, we can carry out some higher-risk experiments in the orbital module after we recover the experimental loads from the other experiments,” Hu said.

Microgravity experiments are normally carried out in various space facilities, such as space stations, shuttles, research rockets and orbiting satellites.

Scientific personnel work at the landing area of the re-entry capsule of China’s first retrievable microgravity satellite SJ-10 in Siziwang Banner, north China’s Inner Mongolia autonomous region, April 18, 2016. [Photo/Xinhua]

So far, only China and Russia have launched recoverable satellites.

“Now, we are researching the possibility of producing reusable satellites, and I hope we can make some progress during the 13th Five-Year Plan,” he said, referring to the 2016-20 blueprint.

Experiments conducted on SJ-10

-- Silkworm embryos were taken into space for a biology experiment designed to observe the embryos’ genetic reaction to cosmic radiation. Although silkworm embryos had been observed in previous research, there was not enough data to know if genetic mutations occurred at different stages of development. This time the researchers divided the embryos into six groups, so that one group stopped developing every two days, providing a better picture of the mutation process over time.

-- An experiment using 6,000 mouse embryos to measure the effect of a gravity-free environment on living organisms found that some of the embryos completed the full development process into blastocysts-a cluster of cells that can be implanted into a womb. It is the first evidence in human history that early-stage mammal embryos can develop in space.

-- Human stem cells are being used for experiments in cell differentiation as part of the satellite’s biotechnology research. Stem cells can differentiate into specialized cells and also produce more stem cells. They are considered a key source for regenerative medicine. The SJ-10 carried experiments on cell cultures of hematopoietic stem cells and neural stem cells, and explored the differentiation mechanism of human bone stem cells.