Taking into account domestic and overseas economic conditions, China may retain its targeted easing in monetary policy in 2015 to avoid a hard landing of the economy, with the possibility of further cuts in both bank reserve requirement ratio and benchmark interest rates, experts say.[Photo/China Daily]

Experts expect nation to play bigger role in global economy by next year.

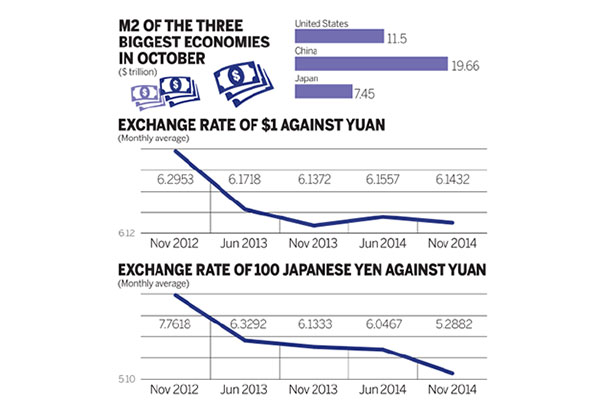

Economists are viewing China’s monetary policy in 2015 as the next beacon in directing global capital flows, as the US dollar strengthens and the Japanese yen weakens.

[Photo/China Daily]

They suggest that the economy will grow in its influence on the world’s economic recovery, as policymakers continue their efforts to strengthen growth at home.

Rather than responding to the actions of the US Federal Reserve and the Bank of Japan, experts prefer to view China’s motivation for rates cut on Nov 21 as being to lower borrowing costs for the real economy and accelerate interest rate liberalization.

The People’s Bank of China, the country’s central bank, announced to lower the benchmark one-year deposit rate by 25 basis points to 2.75 percent and cut the lending rate by 40 basis points to 5.6 percent.

The upper ceiling on the deposit rate was raised to 120 percent of the benchmark rate, up from the previous 110 percent.

Nearly three weeks before that, the Bank of Japan expanded its quantitative monetary easing policy, right after the US Federal Reserve announced it was ending its third round of quantitative easing. Since then the yen has weakened sharply against the dollar leading to depreciating pressures on other Asian currencies.

Economists are concerned that the ongoing depreciation of the yen may rekindle competitive currency devaluation, or a “currency war”, in the region.

Japan’s biggest export competitors, particularly South Korea, may cut their own interest rates further after it lowered its rates twice this year, economists say.

But Louis Kuijs, chief economist in China at the Royal Bank of Scotland, says it is unlikely that the Chinese yuan would depreciate in response to the yen’s fall.

“Competing with Japan is not a major issue in China, as the importance of Japan as an export market has diminished,” he says.

“Aware that China is still growing its share of global trade, the country’s leaders are more concerned about the state of global demand than about its own competitive position.”

Concern has grown after the recent appreciation of the greenback drove up the value of the yuan against most other major currencies.

Learning from the lessons of the Asian financial crisis in the late 1990s, and more recently the 2008 global financial crisis, China prefers to keep its currency value fixed to the dollar, while many other currencies have suffered depreciation or even turmoil in the international financial markets, says Kuijs.

China’s increased influence on the global economic and financial system, says Kuijs, and more specifically, its goal of internationalizing the yuan strengthens its case against engaging in anything that looks like “competitive devaluation”.

A recent report from Singapore’s DBS Group suggested the yen’s depreciation will boost Japan’s real economy but that would only be short-lived.

“Over the past two years, the depreciation of the yen failed to lift export volumes and industrial output proportionately. Structural headwinds and fiscal constraints will continue to weigh on the economy,” it says.

Besides, it pointed out that any rise in Japan’s capital outflows could be a longer-term story, determined by the negative growth and interest rate differentials between Japan and the rest of the world.

In the meantime, China’s current macroeconomic policy is much more focused on supporting domestic demand than exports, as the real estate downturn continues to dampen growth, which may now drop to a historical low.

Zhu Jianfang, chief economist at CITIC Securities Co Ltd, says that China may retain its targeted easing in monetary policy in 2015 to avoid a hard landing of the real economy, with the possibility of further cuts in both the bank reserve requirement ratio and benchmark interest rates.

Given the current sluggish economy, the central bank remains under pressure to bring down financing costs for business borrowers and lower the interbank interest rates.

A research note from JPMorgan Chase & Co has said that the PBOC could make two RRR cuts of 50 basis points each in 2015 to stabilize broader money supply, or M2 growth, which will be accompanied by targeted quantitative easing.

Wang Tao, chief economist in China at UBS AG, says that narrowing interest rate differentials and increasing capital outflows can help drive the yuan modestly weaker against a strengthening dollar amid heightened volatility.

“Although the government wants to avoid exacerbating economic imbalances with an excessively expansionary monetary policy, it also needs to prevent passive tightening in light of slower foreign exchange inflows and tightening shadow banking rules,” she says.

China’s exchange rate policy may become more flexible next year as the internationalization of the yuan is accelerated, says Zhou Shijian, a senior trade researcher at the Center for US-China Relations at Tsinghua University.

The yuan is likely to be a part of the IMF special drawing rights’ basket by 2020, by which time the capital account will be fully opened to the international market and the currency will be freely exchanged, so monetary policy should start preparing for that from now, says Zhou.

Lian Ping, chief economist with the Bank of Communications, says that in the near future, both capital inflows and outflows will be seen, and cross-border funding flows will become more volatile.

“The current environment is complicated,” says Lian.

Besides the effects of an end to the United States’ quantitative easing, the pressure on domestic companies to boost direct overseas investments and measures to lower internal market interest rates will together affect capital flows, he says.

“As Chinese economic growth enters a structural downturn and the international payments surplus narrows, the growth in China’s foreign exchange purchases is expected to slow down in the medium term.”

As the country’s trade surplus rises and domestic investment slows, China is likely to generate large current account surpluses over a prolonged period.

The large scale of surpluses will then transform into capital outflows and be injected into global infrastructural investments.

“China’s fund outflows may keep long-term capital cheap even if the world’s major central banks tighten their monetary policies. How the world absorbs China’s large current account surpluses will define the next round of economic expansion,” says Sanjeev Sanyal, global strategist at Deutsche Bank.

He said that a real appreciation of the yuan is unlikely to correct those surpluses, but could perversely add to them.