Efforts will boost space research capacity

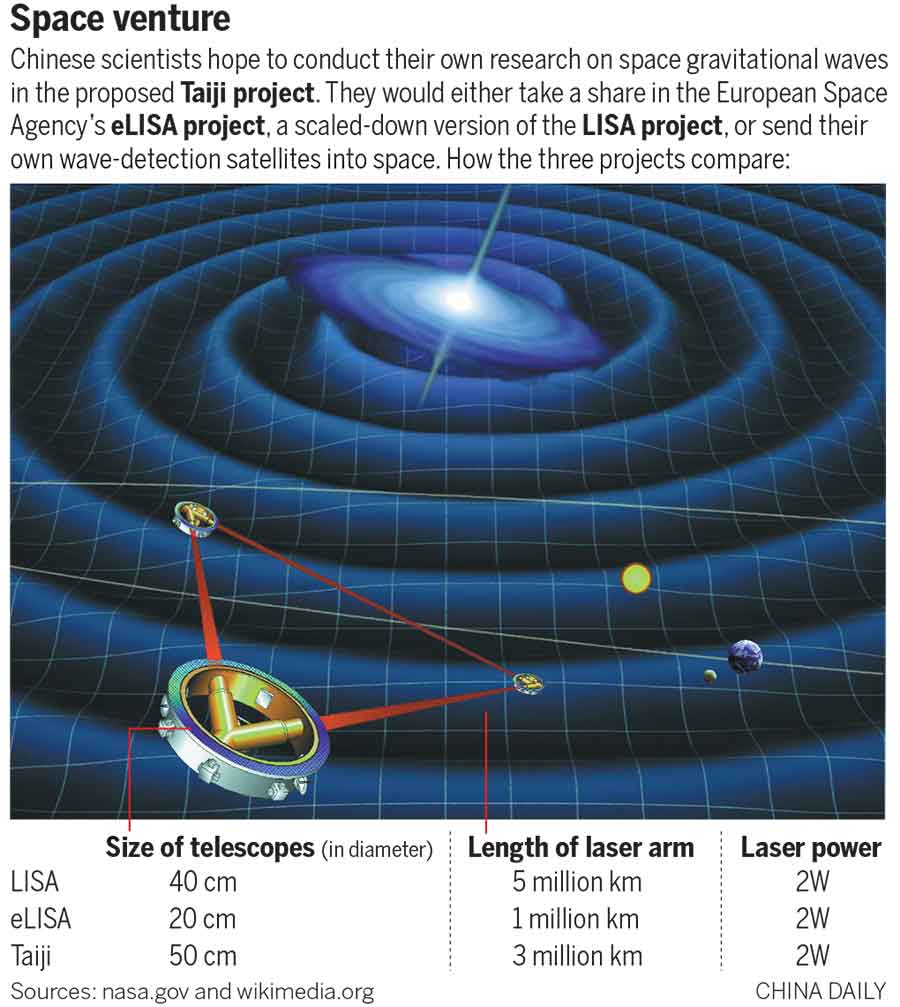

Chinese scientists are proposing a space gravitational wave detection project that could either be a part of the European Space Agency’s eLISA project or a parallel project.

The announcement of the discovery of gravitational waves in the United States on Feb 11 by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory has encouraged scientists around the world, with China set to accelerate research. Gravitational waves are tiny ripples in the fabric of space-time caused by violent astronomical events.

Scientists from the pre-research group at the Chinese Academy of Sciences disclosed that the group will finish drafting a plan for a space gravitational wave detection project by the end of this year and will submit it to China’s sci-tech authorities for review.

The Taiji project will include two alternative plans. One is to take a 20 percent share of the European Space Agency’s eLISA project; the other is to launch China’s own satellites by 2033.

“Gravitational waves provide us with a new tool to understand the universe, so China has to actively participate in the research,” said Hu Wenrui, a prominent physicist in China and a member of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

“If we launch our own satellites, we will have a chance to be a world leader in gravitational wave research in the future. If we just participate in the eLISA project, it will also greatly boost China’s research capacity in space science and technology.

“In either case, it depends on the decision-makers’ resolution and the country’s investment,” he said.

The draft will provide different scenarios with budgets ranging from 1.6 billion yuan ($243 million) to more than 10 billion yuan.

“Although I am not sure which plan the decision-makers will finally choose, I think the minimum budget of 1.6 billion yuan should not be a problem for China,” Hu said. The Laser Interferometer Space Antenna’s gravitational wave observatory was the EAS’ cooperative mission with NASA to detect and observe gravitational waves.

The project, proposed in 1993, involved three satellites that were arranged in a triangular formation and sent laser beams between each other.

Since NASA withdrew from the project in 2011 because of a budget shortfall, the LISA project evolved into a condensed version known as eLISA.

On Dec 2, the European Space Agency launched the space probe LISA Pathfinder to validate technologies that could be used in the construction of a full-scale eLISA observatory, which is scheduled for launch in 2035.

“Currently, all the operating gravitational wave detection experiments worldwide are ground observatories, which can only detect high-frequency gravitational wave signals,” said Wu Yueliang, vice-president of the University of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

“A space observatory, without any ground interference or limitation to the length of its detection arms, can spot gravitational waves at lower frequency.”

On February 11, scientists from the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory in the US confirmed they had detected gravitational waves caused by two black holes merging about 1.3 billion years ago. This was the first time this elusive phenomenon was directly detected since it was predicted by Albert Einstein 100 years ago.

LIGO, currently the most advanced ground facility for gravitational research, includes two gravitational wave detectors in isolated rural areas of the US states of Washington and Louisiana. Meanwhile, the Taiji project of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has competitors in China. Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, proposed the Tianqin project in July.

That project will receive a 300 million yuan startup fund from the local government to initiate a four-step plan to send three satellites in search of gravitational waves and other cosmic mysteries.

Li Miao, director of the Institute of Astronomy and Space Science, said it was still too early to tell the specific direction of the future of the university’s Tianqin project.

“The major gravitational wave research program in China is the cooperation with eLISA, which is led by professor Hu Wenrui,” Li was quoted by Guangdong’s Nanfang Daily as saying.

“The reason that eLISA made progress rather slowly was that the member states in Europe held different opinions as to whether gravitational waves exist.

“Now this has been proved to be true, which will greatly accelerate the pace of research in and out of China,” Li said.