Cui Ruzhuo’s ‘finger-ink’ show opens at the Palace Museum, marking a rare chance for a living artist.

As a teenager, Cui Ruzhuo was engrossed in making replicas of famous artworks at the Palace Museum in Beijing.

Now 72, the contemporary artist has returned to the same venue to display his Glossiness of Uncarved Jade: Grand Exhibition of Cui Ruzhuo.

On Feb 25, the grand opening of his show that runs through June 25 was held at the former imperial site, which is also known as the Forbidden City, marking a rare opportunity for a living artist.

More than 200 sets of Cui’s paintings are on display in the Meridian Gate exhibition hall above the museum’s main entrance.

Cui is known for reviving traditional Chinese painting with his “finger-ink technique”.

The technique, which refers to the use of fingers instead of brushes or other painting tools, was first mentioned in the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-907). Some painters of the mid-Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) used it, and celebrated painter Pan Tianshou (1897-1971) took it to a new level.

“Our predecessors tried almost every technique in traditional Chinese painting, and there is little room left for creativity,” Cui tells China Daily. “However, finger ink is a way out.”

Pan used not just his fingers but also his palms to produce paintings of flowers and birds. Cui expanded it further by using the technique in landscape paintings and even calligraphy.

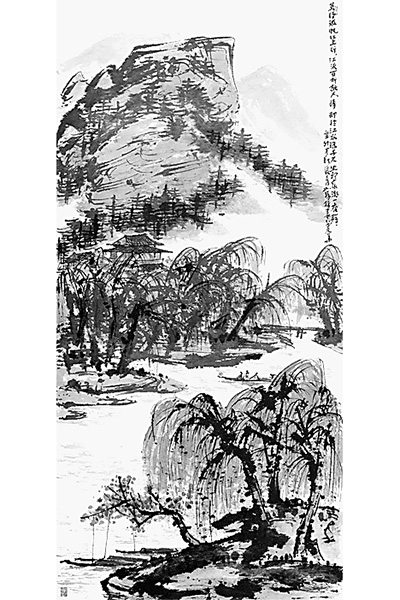

Cui’s solo show in Beijing features more than 200 sets of his paintings, many of which are painted with his unique “finger-ink technique”.[Photo/China Daily]

Highlights of Cui’s ongoing show are such works as the Red Maple and White Snow, the 56-meter-long Forestry Hills with Intoxicating Snow and Poetic Painting of Du Mu.

“The finger-ink technique was originally suitable for small pieces,” says Feng Yuan, vice-chairman of the China Federation of Literary and Art Circles, an industry body. “So, the layouts and structures of Cui’s paintings become unique as the technique moves to such large-scale works.”

Cui, who also uses brushes for some of his works, attributes his inspiration to Shi Tao and Bada Shanren, two prominent Chinese painters from the 17th century.

“Cui’s works are powerful and shocking, but they are harmonious as well,” says museum director Shan Jixiang. “The details are also exquisite.”

About 15 of Cui’s paintings will be permanently displayed at the museum, deputy director Wang Yamin says.

The institution not only houses cultural relics but also records a long list of premier artworks, in a process that can no longer exclude modern masters.

But the museum decided not to collect too many pieces of any one master so as to make it easier for future generations to review them as national treasures, Wang says.

And Cui isn’t just critically acclaimed. The total auction turnover from his landscape paintings reached 470 million yuan ($72 million) in 2014, making him one of the country’s most prosperous living artists.

Last year, he broke his own record when he earned 900 million yuan from sales of his works.

Cui’s solo show in Beijing features more than 200 sets of his paintings, many of which are painted with his unique “finger-ink technique”. [Photo/China Daily]

At the inauguration of his show on Feb 25, Cui announced a donation of 100 million yuan to the Palace Museum to further its efforts at preserving cultural heritage.

He had earned the amount recently from a real estate tycoon, who bought one of his scroll paintings.

Cui has himself collected ancient Chinese paintings since the 1980s.

“It’s not necessary to link an artist’s commercial success with his or her artistic achievements, but Cui has his reasons to be so successful,” says Shao Dazhen, a veteran art critic.

“He pays much attention to the modern development of traditional Chinese painting and, therefore, has a solid basis.”

Born in Beijing, Cui lived in the United States for 15 years, but his works show little Western influence.

“For a Chinese artist, it’s important to see what the gist of our original culture is,” he told reporters at the opening of his exhibition.

“Many Chinese artists try to combine Western and Chinese ideas in art. However, it’s difficult for them to become mainstream,” he says.

“Young generations should better inherit traditions rather than merely use Western criteria.”

Cui says his experience of living in the US in the 1980s and part of the ‘90s has made him better understand cultural diversity.

After stunning the home art market in recent years, Cui is now eager to have his paintings recognized worldwide.

“When I came back to China in 1996, a traditional Chinese painting created in the modern times only sold for a thousand yuan or so and was almost absent from international auctions,” he recalls.

The market began to pick up a decade ago. One of Cui’s works went for 7 million yuan at a Hong Kong auction in 2004.

Vincent van Gogh’s and Pablo Picasso’s works can be easily sold at steep prices, but Chinese artists still lag far behind, he says.

“It’s not only my individual dream but perhaps the country’s dream to surpass them all in terms of market performance.”

Cui hopes to realize that at least by the time he is 80 years old.