The government is preparing to further deepen reform of the national policy on planned parenthood to ensure a stable workforce and continued growth.

Whether or not to have a second child has become a burning and urgent question for millions of Chinese couples who recently became eligible to have two children under the terms of China’s revised family planning policy.

Li Liangyu, a 36-year-old working mother in Beijing, has been discussing the issue with husband since December, when the central government announced the universal second-child policy.

“It needs an urgent answer and action because my fertility is declining due to age, but it’s hard,” said Li, whose 7-year-old daughter entered grade school in the fall.

Money is tight for Li and her husband. Although they are both employed by government institutions and have a combined monthly income of nearly 25,000 yuan ($3,800), their mortgage repayment is 8,000 yuan per month and they pay 3,000 yuan for after-school activities every four weeks.

Like many children, Li’s daughter attends a range of after-school activities, such as learning to play the piano, painting and dancing, which puts further strain on their budget. “With no other source of income, I’m afraid that we can’t afford to have a second child and maintain the same standard of living,” Li said.

The quandary is even more difficult for residents of mega-cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, where a lack of quality educational resources means parents are often required to pay extremely high prices to buy a home in an area with good schools.

“It’s like hell when my son falls ill,” said Liu Min, a 28-year-old mother who is pregnant with her second child. “It’s always so crowed at the children’s hospital, and you are lucky to see the doctor after a three-hour wait.”

According to government estimates, China will see a maximum 9 million more babies in the next three years. “But is the country actually ready to welcome them and treat them well?” Liu asked.

“I would only compromise my present standard of living, such as missing out on an overseas vacation every year, to have a second baby. I want my boy to have a companion to grow up with,” she said.

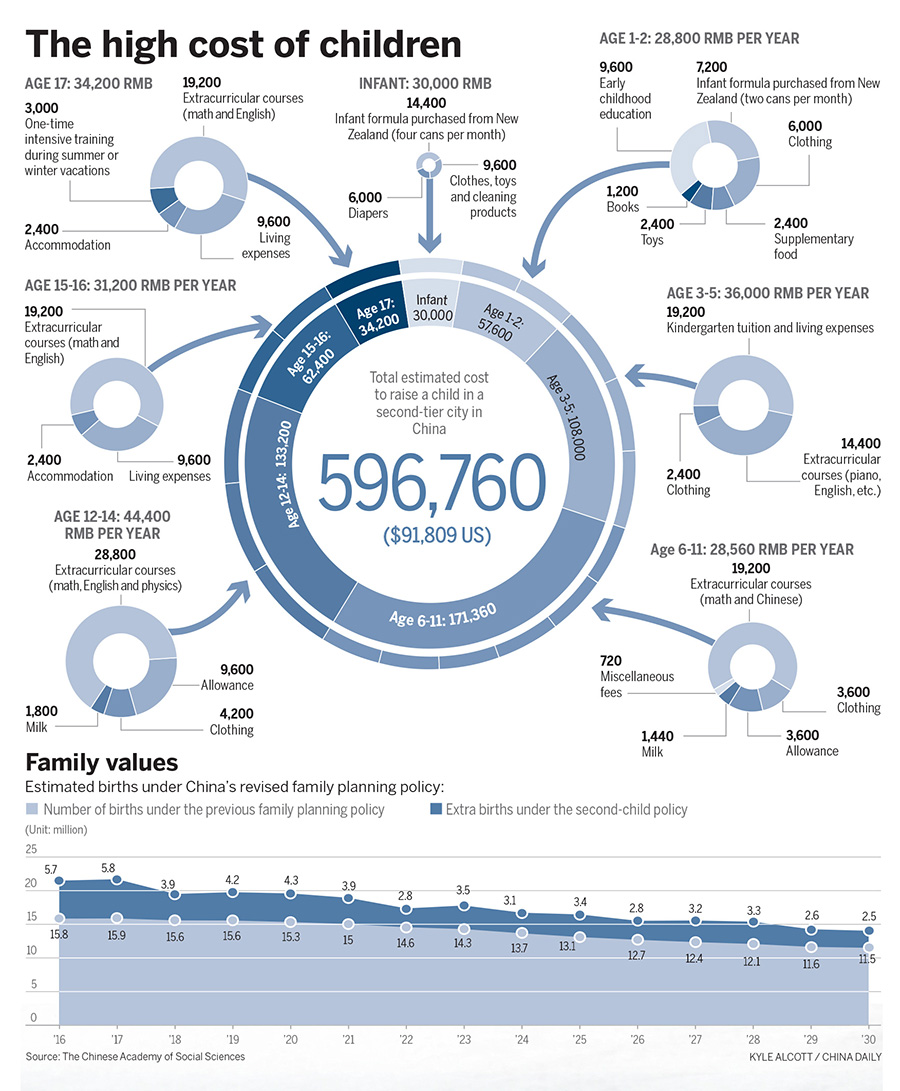

The potential strain on family finances has led many couples to abandon the idea of having a second child. According to a 2014 survey conducted in Guangzhou, Guangdong province, the cost of raising a child until after university averages 2 million yuan in tier-one cities such as Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou.

At the end of 2013, the government made the first move to ease the decades-old policy that restricted most couples to one child. Although the revised rules allowed couples to have another baby providing one partner was an only child, less than 10 percent of newly eligible couples had filed an application by the end of 2014, according to statistics released by the National Health and Family Planning Commission.

Wang Pei’an, the commission’s deputy director, urged other government agencies, such as the ministries of education, finance, and human resources and social security, to draw up favorable measures and policies to encourage larger families.

Demographic changes

Revision of the family planning policy is expected to add at least 30 million people to China’s working-age population by 2050, helping the nation to curb a looming labor shortage, Wang told a media briefing in January.

“It’s not just a population issue but an economic one as well, and that matters a lot for the nation’s overall development,” he said.

By 2050, China’s labor force ages 15 to 59, which has dwindled continuously since peaking at 940 million in 2012, is predicted to reach 700 million, as a result of the new policy.

“The working-age population has been on a seemingly irreversible downward trend, like the population as a whole, but the universal second-child policy could help to slow that decline,” said Yuan Xin, an expert in population studies at Nankai University in Tianjin.

According to demographers, the population will peak at 1.45 billion sometime around 2030, and will then begin to fall. However, the peak would occur two years earlier without the universal second-child policy, he said.

By 2050, the policy will have resulted in an extra 150 million people, bringing the overall population to about 1.38 billion.

“A sustainable supply of human resources is necessary to maintain the nation’s economic growth,” Yuan said.

“The Chinese people have long made a great contribution to the nation’s economic miracle by adhering to the previous family planning policy, which was constantly fine-tuned to assist the overall development strategy,” he said.

He urged the provision of financial incentives for couples who decide to have another child, and for those who suffered under the previous policy, particularly parents who lost their only child to disease or accident.

Tax reform

Authorities have finished drafting a program to reform individual income tax to benefit couples who choose to have a second child, and it will be submitted to the national legislature for review later this year, according to Lou Jiwei, China’s finance minister.

Last year, the Ministry of Finance, the State Administration of Taxation and other related government departments worked jointly on the plan, and it has now been submitted to the State Council, Lou told a press briefing on March 7.

However, the amendment is not just about thresholds, but also considers overall income and expenditures, such as mortgages, school fees and care for the elderly, he said, speaking on the sidelines of the two sessions. Yuan Xin, of Nankai University, also welcomed the reforms. “They are in line with international practice,” he said.

Mu Guangzong, a demographics expert at Peking University, urged the introduction of stronger supporting measures.

“If they aren’t forthcoming, it will be extremely difficult for people to implement the new policy,” he said, adding that financial incentives should be provided for couples with two children. “To have two children is good, and three is even better,” he said.

In addition, the government should improve maternity and child care services, plus related policies, such as risk assessment. Central and local authorities must be prepared to monitor and evaluate the newborn population and the fertility rate to ensure that medical and health resources are properly distributed, he said.

He urged the authorities to learn from the experiences of other countries that have encouraged population growth, saying lessons can be learned from the birth and child-welfare policies in countries such as Sweden, Japan and Singapore, and that they should be trialed in China.

“A helpful national childbirth policy would help to ease the burden on families that want to have two children, which would help to provide a sustainable workforce,” he said.