On March 4, the day before the start of the annual session of China’s legislature, a reporter asked the country’s top legislators why they planned to review the final draft of a new charity law in preference to “more important” legislation.

Given the weighty subjects under discussion at the annual gathering, the question was appropriate, but it also revealed the mainstream Chinese view of philanthropy: For many people, charity is irrelevant to their lives.

However, the draft of a new law that was submitted for review on March 9 aims to regulate and develop the sector, and is expected to provide a vital shot in the arm for charities.

“What has impressed me most is that the draft aims to create a more supportive environment for charitable activities. It will simplify the registration procedures and allow people, resources and organizations with the desire to undertake charitable acts to enter the field,” said Li Jing, secretary-general of the One Foundation, China’s first private charitable fundraiser.

“Meanwhile, supervision will be strengthened to regulate and manage social organizations to prevent illegality,” he said, adding that the new law will promote competition in the sector.

Wang Ming, president of the NGO Research Institute at Tsinghua University and also a member of the National Committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, called the proposed legislation a “milestone” in Chinese philanthropy.

“In the past decade, the boom in philanthropy has mostly been driven by the market, but it has also been driven by society as a whole, including private companies, enterprises and public enthusiasm. But without laws or regulations, problems may arise,” he said.

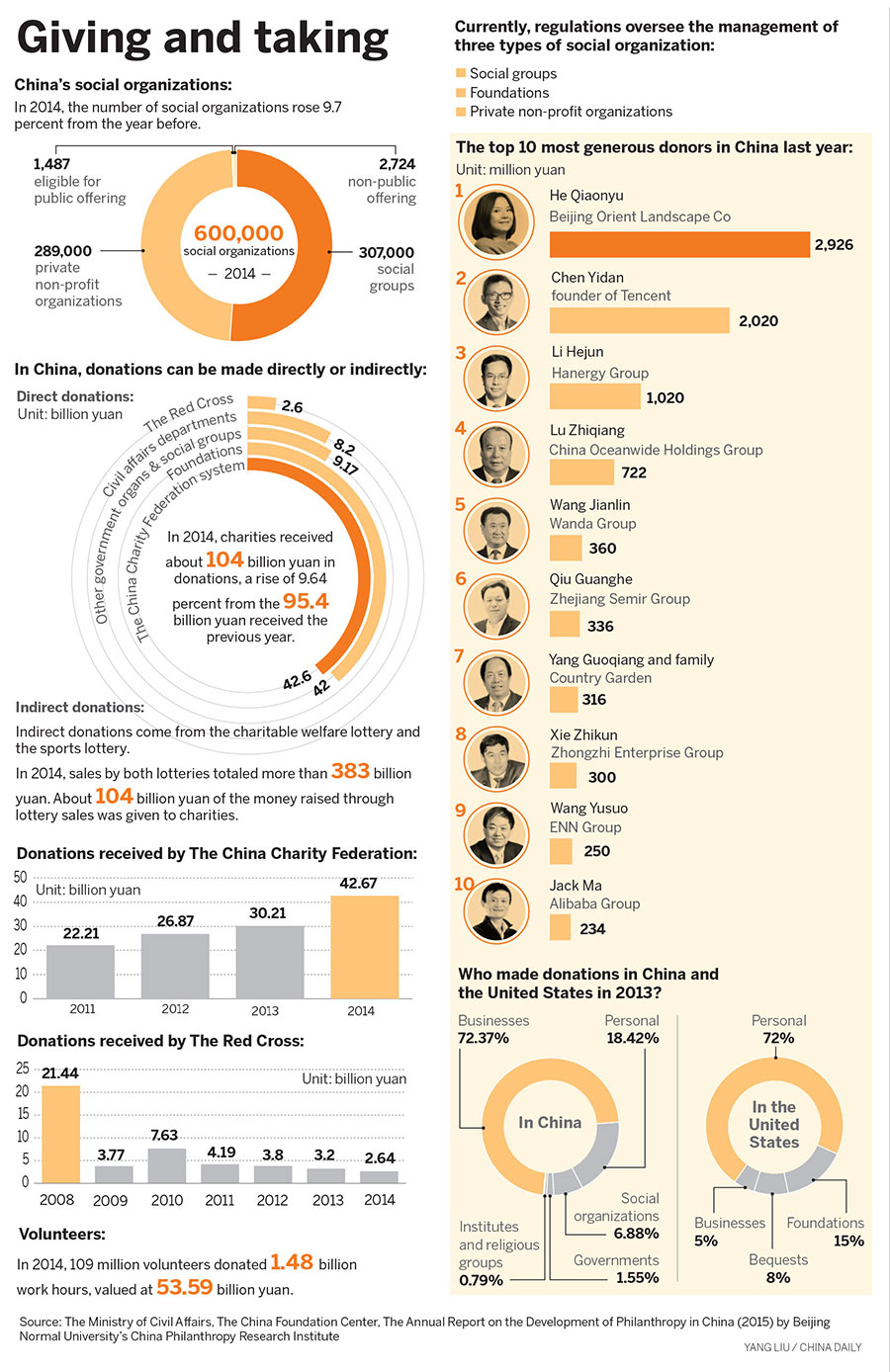

China has more than 600,000 social organizations and 65 million registered volunteers. In 2014, direct donations totaled more than 100 billion yuan ($15 billion), overshadowing the 10 billion yuan donated in 2004.

In response, the government is aiming to standardize the sector. In October, the first draft of the new law was submitted to the National People’s Congress, the nation’s top legislative body, and the second draft was open for public consultation until Jan 31. NPC deputies will vote on the final draft on March 16, the last day of this year’s two sessions.

“The importance of the charity law cannot be underestimated,” said Fu Ying, spokeswoman for the Fourth Session of the 12th National People’s Congress, adding that it will be the country’s first fundamental and comprehensive law on philanthropy.

With the fast development of philanthropy, China urgently needs a comprehensive charity law that will protect the rights of donors and the needy, and punish fraudulent operators, she said.

Negative perceptions

Li Yuling, honorary president of the China Charity Federation, said the sector has been harmed by negative publicity and a poor public image, especially as some entrepreneurs conduct their businesses under the guise of charity, which has resulted in misunderstandings and mistrust.

“What is philanthropy? In many foreign countries, children learn about philanthropy at primary school, but many people in China are still unaware of it or they consider philanthropists to be hypocritical or fake,” she said.

Kan Ke, deputy director of the Legislative Affairs Commission of the NPC Standing Committee, acknowledged the problem: “We have to admit the public has had doubts and lost some trust in the charity sector after a number of donation scandals in recent years. That’s why we decided to solve the problems through legislation.

“We don’t want to see charitable organizations using money donated by the public to fund businesses, neither do we want to see people pretending to be managers of charitable organizations,” he said, referring to a 2011 scandal that prompted a backlash against philanthropic organizations.

The case involved a young woman, Guo Meimei, who posted photos of herself with luxury cars and expensive handbags on Weibo, China’s Twitter-like social media platform. Guo’s claims that she was employed as a manager of an organization associated with the Chinese Red Cross Charity made national headlines as outraged members of the public criticized what they saw as misappropriation of donated funds.

Although it was later revealed that Guo had no links with the charity, public trust had been undermined, resulting in a severe decline in donations to the Red Cross Society of China. The organization still hasn’t fully recovered from the incident. In 2010, the Red Cross received donations totaling 7.63 billion yuan, but the figure fell to 4.198 billion yuan in 2011. Donations continued to decline year-on-year, and in 2014, the Red Cross received just 2.6 billion yuan.

‘One bad apple’

“In the charity sector, one bad apple spoils the whole barrel. Illegal behavior jeopardizes the whole sector, so it’s very important that supervision is strengthened to make philanthropy more popular with the general public,” said Li Jing from the One Foundation.

Kan said the proposed legislation aims to improve the development of the charity sector, raising public awareness and encouraging more people to donate money.

“Over the past few years, the total amount donated annually has been about 100 billion yuan. That may sound a lot, but in fact, it’s not a huge sum,” he said.

According to the 2015 CAF World Giving Index, published in November by the Charitable Aid Foundation in London, Chinese people are reluctant to donate money to charities or volunteer to help. The survey ranked China next from last on a list of 145 countries and regions, only above Burundi.

“The reason lies in the public’s low awareness of charity, and distrust of charitable organizations. We hope the new legislation will regulate the founding, operations and the methods of donation of charitable organizations, because the more regulated the industry is, the more donations we will receive,” Kan said.

Fung Danlai, a CPPCC National Committee member and a former member of the board of the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals, said: “Just as many international NGOs play important roles in helping governments take care of people in need in their countries, it should be the same in China. Charitable organizations should play their roles to care for the underprivileged,” she said.

“Hong Kong has the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals with a history of 150 years, which is the oldest and the largest charitable organization in Hong Kong. Not a single Hong Kong family can say they have never received help from the Tung Wah Group. This is what a non-profit organization should be; the government’s right-hand man, helping people in need,” she said.

A comprehensive legal framework will be an essential factor in improving transparency and funding for social organizations in the Chinese mainland, according to Fung: “Charitable organizations and the people involved should follow the law. It must be planned correctly. Charitable organizations should be run scientifically so they use donations correctly and help people.”

Kan, from the NPC, said the complicated registration procedures for charitable organizations have discouraged both individuals and organizations from joining the sector. The new law has been drafted to reduce red tape and simplify the entry procedure. It also includes a number of favorable tax policies for charitable organizations, and will provide tighter supervision.

“That’s a good thing. After all, the donated money is not the organizations’ money, so they cannot use it as they want. The public has a right to know whether the money is being used effectively,” he said.

According to Li Yuling, from the China Charity Federation, the new law will streamline administration of the sector. “All social organizations are currently required to register with the civil affairs departments, but they also have to register with a related government department, which acts as their supervisor. That’s very inconvenient. The new law will change that, which is good news.”

Li Jing, from the One Foundation, believes the legislation will give organizations greater independence. “There is no doubt that the coming charity law will be excellent news and a milestone in the improvement of philanthropy in China. The draft specifies that charitable foundations and donors will be allowed to enter into agreements about administrative costs,” he said.

Under the current legislation, the cost of administering individual donations, which includes salaries of staff members, cannot account for more than 10 percent of the total annual donation. For example, only 50 yuan of an annual donation of 500 yuan can be set aside for administrative costs. The new law is likely to allow the parties to reach a bilateral agreement on the proportion of a donation that can be used to pay salaries and other expenses.

Interest overseas

The proposed legislation has also attracted attention outside China.

“We see the new law as a very positive development. The proposed law seeks to promote a culture of charity, as well as to protect the rights and interests of charitable organizations, donors, volunteers, beneficiaries and others who work in the field of charity,” wrote Pia MacRae, country director of Save the Children in China, in an e-mail exchange with China Daily.

MacRae emphasized that effective regulation and supervision will boost public trust in the sector: “Our greatest hope for this new law is that it is a catalyst in the further development of China’s philanthropic sector, through both recognizing and encouraging the role that charities can play in social development, while also ensuring that the sector is well-managed and transparent.”

Meanwhile, Diana Tsui, head of Global Philanthropy for Asia Pacific at JPMorgan Chase, said the legislation will provide greater clarity and supervision. “We need reputable and strong local NGO partners to help deliver on commitments. With the new law put in place, our local partners will become more transparent and accountable in delivering impact on the ground,” she wrote in an e-mail to China Daily.

While charity sector professionals have been debating the implementation of the new law, and many NPC deputies have submitted proposals and suggestions during the two sessions, Li Jing said implementation will just be the first step in the process, and charitable organizations will have to play their part, too.

“The big questions that remain are how to carry out charitable activities according to the provisions outlined in the new law, and how to revise the current outdated regulations so they adapt to it. We need to continue looking into them to find the right answers,” he said.