A returnee from the US displays the model trains he sells on his online store in Shanghai.[Photo/China Daily]

For the past two and a half years, Li Guanjiao has spent every day contacting potential investors, promoting her products and brainstorming design ideas with colleagues.

“It’s exhausting, but great fun,” said the 28-year-old budding entrepreneur, in a telephone interview she fitted in between meetings with potential backers.

Li studied for a master’s degree in branding at the London College of Communications from 2012 to 2014, and landed a job in the fashion and design section of a Chinese-language newspaper in the British capital straight after graduation. There, she embraced the United Kingdom’s highly-developed fashion, design and printing industry.

“I noticed that many countries, such as the UK and South Korea, have iconic painting styles of their own, yet Chinese cultural images and designs don’t seem straightforward and iconic enough,” she said, explaining how she had the idea of starting her own company.

Her brand and company is BCZW, which stands for the first letters of syllables of benchuziwu, or “prime meridian”, in pinyin. It produces decorative Chinese designs, which can be screen-printed on mugs, notebooks, hats and T-shirts.

The company, which has about 20 employees, is located near the Today Art Museum in Beijing, where modern art is exhibited and Li can better promote her products.

In addition, she has a major promotion channel via an online store on Taobao.

Li is one of a growing number of young Chinese with experience of working and studying overseas who have returned to start businesses.

Growing enthusiasm

In December, a report published by the Center for China and Globalization and the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences showed that enthusiasm for entrepreneurship has soared among returnees in recent years.

More than 40 percent of students who return to China to start businesses opt to work in large cities such as Shanghai and Beijing. Last year, more than 2.65 million students returned to China.

Li started her business in an entrepreneurs’ incubator established by Renmin University of China in 2015.

“The big advantage was that the incubator provided training about entrepreneurship and taught me many of the basics about starting a business,” she said.

In 2010, China began improving education related to entrepreneurship, and by last year, the Ministry of Education required all universities to open courses on innovation and entrepreneurship.

Many universities, especially those in first-tier cities, also established entrepreneur parks and incubators similar to the one in which Li started her company.

During her first six months at the incubator, Li learned how to approach angel investors, who specialize in funding startups, and institutional investors to give her business a sound start.

“It’s difficult for us to get loans from banks because we have limited assets to use as collateral. Therefore, angels and institutions have become the most important way of raising funds,” she said.

The lack of collateral is a major problem for many young entrepreneurs in Beijing. Some would be reluctant to use their own assets, anyway.

“Even if I bought a house I would not use it as collateral with a bank. If I did that, I couldn’t afford to lose,” said Feng Lizhong, a 31-year-old entrepreneur who registered a shirt brand in Beijing after seven years studying and working in Sydney.

This is where government policies provide assistance. Both Feng and Li managed to secure subsidies from the Beijing government, which provides incentives to encourage returnees to start businesses.

Li received 10,000 yuan ($1,490) when she started BCZW, while Feng was granted the same amount just two months after he started his business.

“To be honest, the money came at a really good time because I had just paid a whole year’s rent for my store and hired my first employee,” he said. “The subsidy helped my business achieve a smoother cash flow.”

About a kilometer from the south gate of Beijing Normal University is an entrepreneurs’ park the university established for returnees in 2005.

It was one of the earliest facilities designed to help returnees start businesses.

Although the park looks a little depilated, Zhou Xin, founder of Beijing Define Technology Corp, is fond of it. He and his team have been located there since 2009, when he left San Francisco to start a company in Beijing.

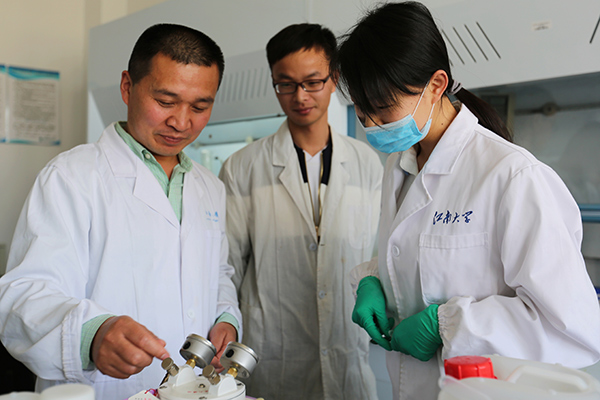

A doctor who returned to Jiangsu province from overseas study shows students how to conduct experiments.[Photo/China Daily]

Business blindness

Back in 2009, the subsidies that helped Li and Feng were not available, and Zhou concedes that he was “kind of blind” when it came to building up his business.

Born in 1976 in Yingkou, a small coastal city in the northeastern province of Liaoning, Zhou holds bachelor’s and master’s degrees from Tsinghua University in Beijing, one of China’s top schools, and also has a doctorate in physics from Stanford University in California, where he studied from 2000 to 2005.

His five years of doctoral research into tunable diode laser absorption spectroscopy technology helped Zhou find a job in Los Angeles, earning $120,000 a year, directly after graduation. Three years later, he had become the company’s chief scientist.

“But that was it. It was a good job. I guess the word ‘scientist’ was listed as a top career when we were little,” Zhou said, with a laugh. “But that’s just it. You can clearly see what your work and life will be in 10 years, in 20 years, by the time you are 60.”

He needed a challenge: “Careers in foreign countries have limitations and ceilings, at least if you are unable to express yourself freely enough due to the language difference.”

Zhou had the idea of starting a company in Beijing while he was watching Win in China, a popular TV program about entrepreneurship. His wife, who has an MBA from Stanford, supported the idea, so they relocated to China, bringing their 18-month-old daughter with them.

The product they had in mind was an advanced gas-detection instrument for use in coal mines.

The device used laser-detection technology, which lowered labor costs and raised the accuracy of detection.

Despite those advantages, the device was a failure because Zhou hadn’t researched the Chinese market before launching it. As a result, he didn’t realize that China’s mining industry was accustomed to using old equipment and there was little desire to change.

“I think the most difficult thing for returnee startups is that your product needs to change customers’ habits. Having lived away from China for so many years, I initially failed to study my target customers’ behavior,” he said.

“The company also lacked marketing channels. Coal mines are located far from Beijing, so the travel costs to introduce the product were huge,” Zhou said.

“All this happened because I had lived outside China for many years so I was unfamiliar with the domestic market.”

In addition, the device had to undergo a large number of tests and reviews before it could be used in coal mines, which took far longer than Zhou had expected.

Meanwhile, protection of his intellectual property rights was another key concern. Those factors prompted Zhou to conduct extensive market research.

Now, his clients are mostly electricity power plants where the device is used to help meet environmental protection standards.

Government policies helped as his company was taking shape. Zhou received more than 2 million yuan in subsidies from the central government and the Beijing municipal government, while the government of Haidian district helped by offering him a lower rent for his business premises.

A farmer with several years’ experience of keeping sheep in the US founded a sheep farm in Hebei province last year.[Photo/China Daily]

Prime location

Unlike many young entrepreneurs, when 33-year-old Zhang Yunfei started his business, in 2010, he chose to locate the company in Zhuhai, a coastal city in South China’s Guangdong province.

Zhang, who has a master’s in mechanical engineering from the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, chose Zhuhai for three reasons: lower costs; the financial incentives provided by the local government; and location, because his work concentrated on the research and development of unmanned surface vessels and submarines.

“The incentives are not as mature as other countries’, but government support is growing rapidly compared with other countries, especially support for science-tech innovation businesses,” said the founder of Zhuhai Yunzhou Intelligence.

In April, the State Council, China’s Cabinet, issued guidelines about comprehensive support for returnee startups. At present, about 350 entrepreneur parks around the country house 27,000 companies and 79,000 returnees.

‘Pace and people’

Pierre Bi cofounded Aeris Cleantec, which makes “next-generation” residential air conditioners, in Beijing last year. He thinks young entrepreneurs are attracted to China because of “the pace and the people”.

“Europe is too comfortable. Most people avoid challenges because they want a steady career path,” said the twenty-something Swiss citizen, whose father hails from the Inner Mongolia autonomous region.

“Right now, it’s summer in Europe, so nothing is really moving. Here, people are aware of what it means to work with a startup, which means long hours and great uncertainty.”

His business partner, Liu Shuo, a 34-year-old Chinese, used to work for a Belgian brewing company.

The pair met overseas and then decided to move to Beijing because they believed their fledgling company would have a great future in the capital.

“China is moving away from traditional economic drivers to consumption-led businesses with a strong focus on entertainment and health. I am pretty confident that the shift will continue,” Bi said.