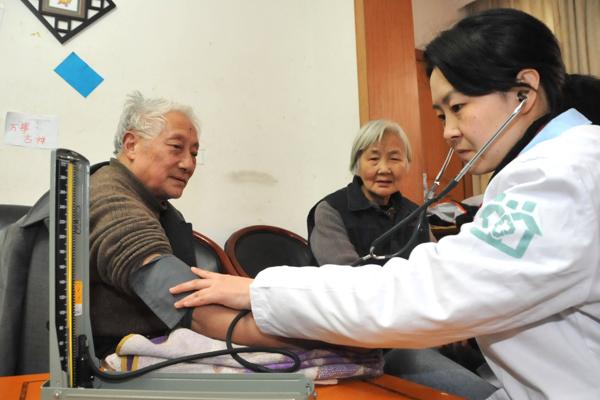

A family doctor measures the blood pressure of an 82-year-old man at his home in Chengdu, capital of Sichuan province.[Photo/Xinhua]

Wang Yucai sat in the two-story building of the Yulin Community Healthcare Center in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province, and chatted like an old friend with his family doctor about a recent trip to Beijing.

The 76-year-old retiree described himself as a “big fan” of Dr. Jiang, with whom he signed a “health contract” last year to help manage his diabetes and maintain his health.

They meet at least once a month, usually when the senior renews his prescription, but Wang also attends health lectures given by Jiang, particularly those about nutrition.

“I learned about and now practice the ‘rainbow’ diet, which highlights the use of colorful vegetables and low-sugar fruits, and emphasizes reduced levels of salt and oil,” he said.

With Jiang’s help, Wang has quit smoking and mahjong, a traditional Chinese game where players spend long periods sitting down, and joined other seniors in a formation-dancing team.

He is an early beneficiary of China’s latest healthcare reform, an initiative that aims to provide all citizens with access to family doctor services by 2020.

According to a State Council guideline released in early June, pregnant women, the elderly, children and those with chronic diseases are the prime targets of the new system. The initiative will make medical services more accessible to the general public and reduce overall medical costs, said Qin Kun, a healthcare-reform official at the National Health and Family Planning Commission.

At present, people visit large hospitals for treatment of minor problems. For many, consultations with specialists are both unnecessary and costly. “Family doctors will serve as gatekeepers for both public health and medical cost control,” Qin said.

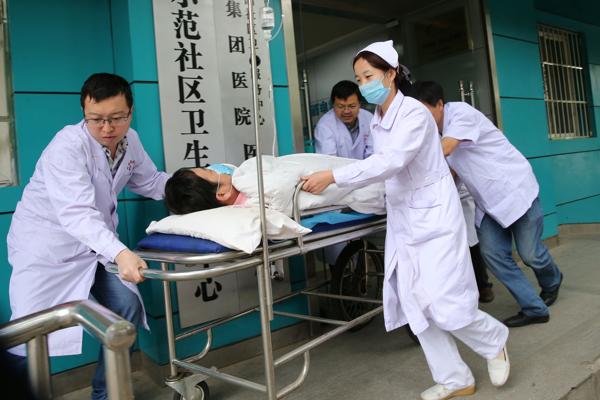

Medical staff at a community health center transfer a patient to a hospital in Xi’an, capital of Shaanxi province.[Photo provided to China Daily]

Patient-centered plan

Family doctors deliver a range of patient-centered services. In addition to diagnosing and treating illnesses, they also provide preventive care, including routine checkups, risk assessments, immunizations and tests, in addition to counseling about maintaining a healthy lifestyle.

They also manage chronic illnesses, often coordinating care with specialists in large hospitals. From heart disease, strokes and hypertension, to diabetes, cancer, and asthma, family physicians provide ongoing, personal care for the nation’s most serious health problems.

Zeng Ling, head of the Yulin center, said their work focuses on general health, not just specific illnesses.

In addition to treating ailments, “we help keep people healthy”, she said. “Therefore, prescriptions not only include drugs, but also health education and behavioral intervention, such as helping patients to quit smoking, eat healthily and exercise.”

The center has 26 doctors, 13 specialists and 13 family doctors, all trained general practitioners. Each family doctor is paired with at least two nurses to provide services for a maximum of 2,000 locals.

Patients are allowed to choose their own doctor, and can contact them via phone calls or through WeChat, China’s leading social networking platform.

The system, which came into operation last year, now covers 30 percent of the 10,000-strong local population, Zeng said. Primary tasks include health consultations and referrals to specialists.

Patients such as Wang, who have chronic diseases, can visit primary care institutions for follow-up treatment, such as repeat prescriptions.

“It’s much more convenient and cozy here compared with large hospitals, which are always crowded,” Wang said.

Zeng said that in severe cases-”those we cannot handle”-patients are referred to specialists, and sometimes consultations take place online.

Xu Yong, a family doctor at the Anjing Township Healthcare Center in Pixian county, about two hours’ drive from Chengdu, has helped patients find the right specialist, and set up remote consultations via a telemedicine system, removing the need for bedridden patients to travel long distances.

Xu and his team have signed contracts with more than 2,000 residents in the nearby village of Yongdu.

“I often receive calls at 6 am, usually from seniors,” he said. “They may be about conditions such as insomnia, flu or headaches, and I suggest treatment based on the patient’s situation.”

He recommends behavioral intervention for chronic conditions: “It works, and saves the patients money.”

The team also organizes monthly health lectures, whose topics vary according to demand. The average attendance is 100 people, according to Xu.

“Family medicine involves a lot communication,” he said.

Big data

Zeng said the government’s target is demanding: “With the current staff numbers and our workload, it will be hard to provide cover for all 10,000 residents by 2020.”

Luo Xiaolu, deputy director of the Tiaosanta Community Healthcare Center in Chengdu, sees big data as a means of providing precise, effective group health management.

The center has installed a software-based, internet-enabled system to track the conditions of contracted patients.

“Analysis of big data will help to improve the family doctors’ working efficiency and deliver better-targeted care for the population,” she said. “Big data facilitates evidence-based group management of patients.”

The center has pioneered the distribution of wearable devices, such as electronic wristbands, which allow patients’ physical conditions and exercise levels to be monitored. It also provides tailor-made service packages, which cost 800 to 1600 yuan a year and are not subsidized.

Shen Haiying, a divisional director at the Wuhou District Health and Family Planning Bureau, which oversees the center, said community health units are encouraged to design a range of optional service packages targeting different groups and requirements, such as newborn care, home services for the elderly and chronic-disease management.

“These are supplementary and people can choose to buy them,” Shen said, although she stressed that the basic service will remain free because it is covered by a government subsidy of 50 yuan ($7.50) a year for every citizen.

Chen Bowen, deputy director of the Community Health Association of China, said the subsidy alone will not sustain the family doctor system, and suggested that State-owned public health insurance programs should join with the health authorities to promote the initiative. That would give both patients and doctors an incentive to embrace the new system, which is used in many Western countries.

If grassroots hospitals can provide a level of care that means patients don’t feel the need to visit large hospitals, the nation’s total medical costs would be lowered substantially, he added.